Scientists have made another stride towards curing treatment-resistant depression (TRD). According to Mercury News, a team at the University of California at San Fransisco (UCSF) successfully implanted a small battery-powered device, about the size of a matchbook, in a woman’s brain and used it to conduct electrical signals that resulted in a lifting of her depression. The beneficiary of the device, Sara, is 36 years old and had been suffering from TRD since she was a child, meaning she has been unable to find relief from her suffering.

So debilitating was her bouts of depression that Sara had all but given up hope, saying, “I was at the end of the line. I was severely depressed. I could not see myself continuing if this was all I’d be able to do, if I could never move beyond this. It was not a life worth living.” The technique used, Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS), is not new, but the incredible success in this case is groundbreaking because DBS has previously not delivered consistent positive results with regard to treating depression. As Science Alert reports,”. . . results on deep brain stimulation for depression that targets particular regions of the brain . . . have been mixed, and mostly underwhelming.”

In fact, many scientists were beginning to give up on the idea of DBS as an effective treatment for depression. The authors of the article Does DBS Have a Future in Depression Treatment? from Psychiatric News state that in one experiment, “the data gave no indication that DBS was helping the 30 depressed patients who had received the treatment,” and moreover, “the participants who did not receive active stimulation had a greater reduction in depression symptoms than those who received active stimulation.” The authors also cite a separate study examining DBS for treatment-resistant depression called BROADEN which “suggested that the therapy was not demonstrating any effect.”

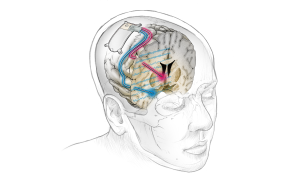

Source: (Ken Probst/UCSF)

.sciencealert.com/

But Helen Mayberg, M.D., director of The Nash Family Center for Advanced Circuit Therapeutics at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and lead investigator on the BROADEN study, pushed for more research, saying, “We have seen about 50% of our patients respond after two years, and about 70% after four years. If you got better, you stayed better.”

Yet, while this long-term benefit, which was seen in at least some patients, is laudable, having to endure depression for that length of time is impractical, especially for people with more severe forms of depression. That’s because living with severe depression puts you at risk for a host of other problems, including social isolation, work-related issues, as well as jeopardizing personal relationships. In the most severe cases, depression can lead to attempts at suicide.

That’s what made this recent breakthrough so important because the UCSF team was able to modify the technique using biomarkers to make it more effective. Interesting Engineering explains it this way:

“After identifying the biomarker, the researchers implanted one electrode lead into the brain area where the biomarker was discovered, and another into the patient’s ‘depression circuit.’ Then, they customized a new DBS device to respond only when it recognizes the specific pattern of brain activity, which enabled them to modulate the circuit. With the implanted device in, the first lead would detect the biomarker, while the second would generate a small amount of electricity deep in the brain for six seconds.”

Specifically, the DBS device used in the study was adapted from one used to treat epilepsy. According to ARS Technica, when the device “detects the biomarker in the amygdala, it sends tiny electric pulses to another area, the ventral striatum, which is part of the brain’s reward and pleasure system,” which in turn “immediately lifts the unwanted mood symptoms.”

The results were immediate and profound. As Sara stated, “In the early few months, the lessening of the depression was so abrupt, and I wasn’t sure if it would last. But it has lasted.” In fact, the depression did not return in the 15 months that Sara wore the device. This was confirmed through the use of a psychological assessment known as the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), which measures depression using scaled scores derived from multiple measures. In Sara’s case, she scored 36 out of a maximum of 45 points on the MADRS, which indicates clinical depression. However, after the modified DBS, Sara’s score dropped to 14, then several months later to 10, indicating a full remission of symptoms.

This could be a game-changer in the treatment of TRD. As Andrew Krystal, PhD, professor of psychiatry and member of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences points out, “This study points the way to a new paradigm that is desperately needed in psychiatry. We’ve developed a precision-medicine approach that has successfully managed our patient’s treatment-resistant depression by identifying and modulating the circuit in her brain that’s uniquely associated with her symptoms.”

Although Sara’s results are promising, much more work news to be done in order to be able to successfully generalize the approach to future patients. Katherine Scangos, MD, PhD, a member of the UCSF team that treated Sara, said, “There’s still a lot of work to do. We need to look at how these circuits vary across patients and repeat this work multiple times. And we need to see whether an individual’s biomarker or brain circuit changes over time as the treatment continues.”

Still, this advance holds great promise for people whose depression does not respond to traditional psychiatric pharmacology. Along with the use of psychedelics, we are sitting on the precipice of being able to help many more people than we could previously.

*Depression is a serious challenge. If you feel you need to talk with someone about your depression, use this link to find telephone numbers of organizations that can help you.