Just to be clear about my overall perspective, I am a committed free-market guy. After all, capitalism is a dance between employers and employees, and the music is always playing. As a young man, I worked a number of jobs that paid relatively low wages, and I come from rather modest means, as my parents struggled to keep my brother and me in the middle class. And I don’t begrudge wealthy people for amassing fortunes; kudos to them. I also don’t necessarily believe taxation is the underlying answer to all of the economic disparity we are witnessing. Rather, I embrace a philosophy that the private sector, with the right incentives and conditions, along with a strong work ethic, can create the positive change for American workers that is so sorely needed. As JFK, who actually cut taxes said, “a rising tide raises all boats.” With that in mind, please read on.

Although wages are not everything when it comes to job performance, it turns out they are pretty damn important after all. That’s at least what Charles Watson, CEO of Tropical Smoothie Cafe, and others, found out, first hand. Watson puts it plainly, stating, “Our franchisees that run the best cafes and have the best hospitality and the best people, they pay more. It’s pretty simple that way.”

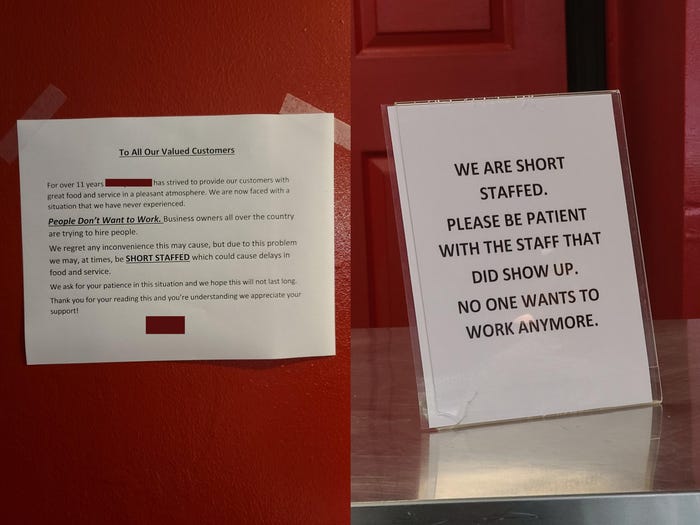

In an economy in which it is becoming increasingly difficult to find employees, especially in the service and hospitality sectors, wages have become a hot-button issue, resulting in the phenomenon of “rage quitting.” Essentially, rage quitting is reaching such a level of frustration with your job because it doesn’t meet your basic economic needs, such as housing, food, and, essential medical care, that you quit in a stylistic temper tantrum.

“By the time you get down to that lowly stay-at-home mom that just wanted a part-time job — who is earning less than a hundred dollars a week because she’s making $7.25 an hour and only working 10 hours a week — it’s not worth it,” Kendra told Business Insider recently. Kendra’s frustration is actually part of a larger movement among younger workers, particularly Millennials, who feel the current job market is not doing its level best to attract and retain employees.

In fact, as cited in inc.com: “According to the Gallup Organization, Millennials are the least engaged generation at work–with only 28.9 percent of U.S. Millennials engaged in their jobs. That means 71 percent are not.”

Of course, this goes beyond mere pay and looks at more qualitative aspects, such as company culture, the quality of benefits offered, and how flexible employers are about taking time off. This presents a huge challenge to companies that seek to build and maintain a competent, loyal workforce.

As Scott Pitasky, Executive Vice President and Chief Partner Resource Officer of Starbucks says, “The workforce of today is more diverse, complex, and challenging than ever before. Over the next 10 years, organizations big and small may succeed or fail based on how they embrace the Millennial generation.”

All of this gets a bit complex due to the changes wrought by the pandemic. With many students stuck at home, at least in the initial phases of the pandemic, lack of access to childcare became a significant challenge to people on the lower end of the economic ladder. Seasoned journalist Ben Gilbert argues, “The ongoing corona virus pandemic has been the catalyst for a variety of huge changes in the labor market, including a drastic decrease in women — especially women of color — participating as a result of lacking access to childcare and major retailers like Amazon hoovering up available workers with higher wage minimums.”

This phenomenon has broader implications, and is known as “economic dislocation,” which according to the Cambridge Dictionary is “a situation in which a person or thing, such as an industry or economy, is no longer working in the usual way or place.” In plain-speak, rapid societal changes pull the proverbial rug out from under workers, especially the service sector and blue-collar workers. The reality is there are a variety of forces, ranging from globalization to displacement caused by emerging technologies, to a lack of skills and knowledge on behalf of job seekers, that have set in motion large-scale economic dislocation patterns. Here are some grim figures from The Peterson Institute For International Economics:

- Between 1995 and 2004, approximately 16 million jobs were terminated each year. Four million terminations resulted in serious unemployment.

- Between 1995 and 2004, approximately 690,000 firms closed each year, affecting 6.1 million workers. An additional 1.7 million firms contracted each year, affecting 11.8 million workers

- Between 1996 and 2007 there were on average 16,400 mass layoff plant-closings each year, affecting 1.8 million workers

While these trends put downward pressure on the vast majority of American workers, they are particularly onerous to people from more meager economic backgrounds. Consider this, also. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2017, 80.4 million workers age 16 and older in the United States were paid at hourly rates, representing 58.3 percent of all wage and salary workers.

Source: Kevin Greenlee/Business Insider

That’s slightly more than 50% of our workforce. And, when other periodic, but significant events occur, such as the housing bust and recession in 2008 and the current pandemic, the force of economic dislocation is compounded, impacting the most vulnerable. These downward macroeconomic pressures, when combined with a negative work environment and low pay, create a volatile cocktail that pushes some workers to their psychological limits, hence “rage quitting.”

Not surprisingly rage quitting has become something of a national refrain for fed-up workers, and examples abound on social media. The fact that social media is involved pushes some workers to create elaborate plans to quit so they can publicly share the moment.

Diara Townes, a program manager at the Aspen Institute who has studied narratives and patterns of spread, sheds some light on this phenomenon, saying “I suspect this is a mix of media amplification of critical opinions of Millennials/Gen Z workers who want to change what work is and the growing job shortage.”

It would be easy to dismiss these workers. Labels such as “unmotivated,” “disloyal,” or even just old-fashioned “entitled” come to mind. And in some cases, this is true.

As reported in Forbes, in a “ . . .study from the University of Hampshire, Millennials born between 1988 and 1994 scored 25 percent higher in entitlement-related issues than their 40-60 year old counterparts, and 50 percent higher than those over 60. The score was calculated using a survey comprised of several questions meant to reveal attitudes of entitlement, such as asking whether participants felt they deserved certain things or asking how superior they felt to others.”

This “entitlement complex,” for lack of a better word, leads to a host of negative behaviors, including unjustified rule-breaking, wanting special privileges other employees don’t receive, and acting in a selfish manner that puts their personal needs ahead of the company and co-workers, according to Forbes.

And to be honest, no one likes a wimpy, whiny, narcissistic worker who feels the whole world is there to cater to their needs and wants but isn’t simultaneously interested in proving their value through job performance. I have several friends who work in supervisory positions and manage Millennials as well as younger workers. They often tell me stories of how privileged these workers can act, and how frustrating this can be.

Moreover, there is a solid argument to be made that minimum wage jobs were never meant to supply a “livable wage” (whatever that means), much less all of the perks that go with jobs that took many people years to acquire. And if the best efforts on part of an employer to positively address these issues fail, he or she is well within their rights to fire underachieving or uncooperative employees. After all, some of the best lessons we learn in life are often the most painful. It’s just part of growing up and taking full responsibility for yourself as a person.

Still, I suspect there is something we can learn from this dynamic of ever-growing workplace dissatisfaction. People want to feel valued, not just for their inherent worth, but for what they bring to the table as a worker. For better or worse, part of what makes people feel value in a market-driven economy is the wage they are paid.

Evren Esen, director of The Society for Human Resource Management [SHRM’s] survey programs points out, “Many workers over the last decade have been frustrated by stagnant wage growth. Younger workers may be particularly focused on compensation as they pay off college loans and try to establish their savings so they can purchase homes and start families. So while factors such as respectful treatment and trust remain important, compensation is a critical job satisfaction factor—especially among Millennial and Gen X employees.”

The bottom line is that COVID-19 has changed things with regard to how prospective and current employees view jobs. So, if employers want to attract and retain better employees, they need to put their money where their mouth is. As Michael Lastoria, CEO of &pizza, a restaurant chain in Washington that pays its employees $16 an hour (resulting in a flood of applications) reminds us, “If you aren’t paying your employees enough to cover basic survival costs, what possible incentive could a person have to take that job?”

And building on what Lastoria has accomplished, one more thing bears exploring. For franchise owners, the reality is that profit margins are often razor-thin, thanks to overhead costs and payment of a myriad of franchising fees, not to mention taxes. In these cases, corporate leaders need to take the burden and find a way to share these costs, because they are ultimately in their best interest as well. If not, they have no right to expect a quality workforce.

Dan Price, the CEO of Gravity Payments who slashed his own salary significantly to give raises to his employees points to an ugly truth: “People are starving or being laid off or being taken advantage of, so that somebody can have a penthouse at the top of a tower in New York with gold chairs,” Dan said. “We’re glorifying greed all the time as a society, in our culture. And, you know, the Forbes list is the worst example – ‘Bill Gates has passed Jeff Bezos as the richest man.’ Who cares!?” Indeed.

At Newsweed.com, we adhere to three simple principles: truth, balance, and relatability. Our articles, podcasts, and videos strive to present content in an accurate, fair, yet compelling and timely manner. We avoid pushing personal or ideological agendas because our only agenda is creating quality content for our audience, whom we are here to serve. That is why our motto is ”Rolling with the times, straining for the truth.”

Your opinion matters. Please share your thoughts in our survey so that Newsweed can better serve you.

Charles Bukowski, the Los Angeles beat poet that captured the depravity of American urban life once said, “There is something about writing poetry that brings a man close to the cliff’s edge.” Newsweed is proud to stand in solidarity and offer you a chance to get close to the cliff’s edge with our first Power of Poetry Contest. Are you a budding bard, a versatile versifier, a rhyming regaler? Do you march to the beat of iambic pentameter, or flow like a river with free verse? If so, here’s your opportunity to put your mad poetic chops to the test. Enter our poetry contest for bragging rights and an opportunity to win some cash!