There is a glimmer of hope that marijuana will be decriminalized at the federal level. According to High Times, “Two U.S. senators recently sent a letter to Attorney General Merrick Garland urging the Department of Justice to decriminalize cannabis at the federal level,” a signal that attitudes towards marijuana may be softening in D.C. Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey and Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts wrote “Decriminalizing cannabis at the federal level via this descheduling process would allow states to regulate cannabis as they see fit, begin to remedy the harm caused by decades of racial disparities in enforcement of cannabis laws and facilitate valuable medical research.”

As posted on Senator Warren’s official government website, the senators reasoned, “the Attorney General can remove a substance from the CSA’s list, in consultation with the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), based on the finding that it does not have the potential for abuse,” pointing out that “To date, thirty-six states, four territories, and the District of Columbia have legalized cannabis for medicinal purposes, and eighteen states, two territories, and the District of Columbia have legalized cannabis for adult recreational use. These state-level legalizations have not caused spikes in traffic accidents or violent crime, or use by teenagers, paving the way for much-needed action at the federal level.”

By taking this route, the senators are effectively bypassing federal legislation that has stalled out in Congress. As I reported in Newsweed, the Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Act, the Marijuana Justice Act, and the Marijuana Opportunity, Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act have failed to advance in the Republican-controlled Senate. The truth is that the illegal status of marijuana at the federal level has been problematic because it pits states’ rights under the concept of federalism against a federal government that has played a significant role in the war on drugs.

This chasm between the federal government’s prohibition against marijuana and the push for legalization at the state level has also hampered having a uniform approach to rationally, evenly, and fairly enforcing laws, resulting in an ad-hoc approach at the local level. The Marijuana Times explains it this way: “With the federal government refusing to budge when it comes to marijuana, a state-by-state strategy was the most likely option for success. Since voters and lawmakers and government officials decide in each state what the law will be, not only are there variations from state to state, but also from jurisdiction to jurisdiction within a state.”

Take the case of Nantucket, Massachusetts, for example. Although weed is legal in Massachusetts, Nantucket is an island, which causes shipment and distribution issues. As Politico points out, “since cannabis products cannot cross federal water or travel through federal airspace to reach the island, the production, testing and sale of cannabis on the island must be completely self-contained.”

Moreover, even federal laws that limit the reach of the federal government exist in a tentative nature. A case in point would be the Rohrabacher–Farr amendment, legislation first introduced by U.S. Rep. Maurice Hinchey in 2001, which prohibits the Justice Department from spending funds to interfere with the implementation of state medical cannabis laws. Unfortunately, however, this law has to be renewed each fiscal year, making it vulnerable to being effectively repealed, or a the very least, reinterpreted.

There is historical evidence for this notion. As CanaCon reports: “In 2015, The Justice Department continued to prosecute medical cannabis patients. This lead to demands in July 2015 for a government investigation into the primary operatives in this, as an act of harassment against medical marijuana patients and providers. It took only 3 months for US District Judge Charles Breyer to affirm the intention of this amendment. The decision criticized the DOJ interpretation. Judge Breyer said that it ‘defied language and logic’ as well as that it ‘tortures the plain meaning of the statute’.”

Judge Breyer knew what we all plainly understand: that an assault on medical marijuana is nothing more than a prelude to a general attack on cannabis, a cleverly disguised attempt to unravel the hard-fought-for progress that has been made through blood, sweat, and tears. Because without a broad federally mandated legalization, or at the very least, decriminalization, the future of marijuana is always in jeopardy.

The most recent example would be the relaxing of marijuana prosecutions under President Obama that was undone by the Trump administration, who used the executive peorogative of enforcement more aggressively by empowering his Attorney general, Jeff Sessions, to go after violators. As Justice Clarence Thomas, hardly a bastion of liberalism, so painfully yet articulately argued, “A prohibition on intrastate use or cultivation of marijuana may no longer be necessary or proper to support the federal government’s piecemeal approach.”

When you step back and look at the whole sordid mess, it is the federal government that has been the wellspring of conflict and unrest, going back more than 100 years. On June 29, 1906, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act and it was signed into law the next day by President Theodore Roosevelt. Passing with an enormous margin of votes in the House of Representatives (240–17), the act stated its intention was to prevent “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of adulterated or misbranded or poisonous or deleterious foods, drugs or medicines, and liquors” according to the Office of Art & Archives of The U.S. House of Representatives.

Although the Pure Food and Drug Act, which was expanded in scope through several amendments, had been created primarily in reaction to the outrageously dangerous and incredibly unsanitary practices of the meatpacking plants as exposed by the novel, The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair, marijuana become conflated with these unsavory practices. The genesis of marijuana’s inclusion in the act comes from Dr. Harvey W. Wiley, a chemist whose main focus and work since 1880 was improving food purity, and author of the initial drafts of the Pure Food and Drug Act.

Source: nymag.com

Wiley rightfully pointed out: “America’s marketplace was flooded with poor, often harmful products. With almost no government controls, unscrupulous manufacturers tampered with products, substituting cheap ingredients for those represented on labels: Honey was diluted with glucose syrup; olive oil was made with cottonseed; and ‘soothing syrups’ given to babies were laced with morphine.”

But, while Wiley’s focus on cleaning up the food and growing drug industries was valid, if not laudable, his statement that ““coffee drunkenness is a commoner failing than the whiskey habit… This country is full of tea and coffee drunkards . . . the most common drug in this country is caffeine” should give us pause and insight into the irrational apprehension that recreational marijuana had any connection to these concerns.

As a result of Wiley’s work combined with the false hyperbolic hysteria induced by the now-cult classic movie, Reefer Madness, almost every state had passed anti-marijuana laws just three decades later. Feeling the need to show leadership, the federal government passed the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, which was steeped in racist intent. Although proffered as a national health and safety issue, its anti-marijuana stance was a carefully targeted campaign against Mexican immigrants.

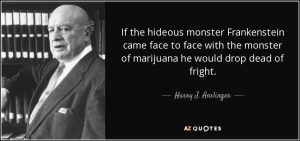

The author of the act was none other than Harry Anslinger, the Commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics during the prohibition era. When prohibition was repealed, Anslinger turned his zeal and angst about alcohol into a fevered campaign against marijuana, mixing it with a healthy dose of xenophobia to give it a broader cultural appeal.

The article The racist origins of marijuana prohibition, by Alyssa Pagano, paints a disturbing but accurate picture of Anslinger’s true motives:

“Harry Anslinger took the scientifically unsupported idea of marijuana as a violence-inducing drug, connected it to black and Hispanic people, and created a perfect package of terror to sell to the American media and public. By emphasizing the Spanish word marihuana instead of cannabis, he created a strong association between the drug and the newly arrived Mexican immigrants who helped popularize it in the States. He also created a narrative around the idea that cannabis made black people forget their place in society. He pushed the idea that jazz was evil music created by people under the influence of marijuana.”

In fact, Anslinger himself wrote patently false claims about marijuana in his 1937 article, Marijuana, Assassin of Youth, stating, “How many murders, suicides, robberies, criminal assaults, holdups, burglaries and deeds of maniacal insanity it causes each year can only be conjectured.”

The irony, or course, is the “maniacal insanity” of the police state we have used to strip people of their rights and incarcerate them, creating a river of misery and a bloodbath saturated with innocent lives, lives that are disproportionately people of color, though that is finally changing, at the state level, at least.

Source: azquotes.com

There was pushback in official scientific circles to the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, including The American Medical Association, which wrote:

“There is no evidence, however, that the medicinal use of these drugs has caused or is causing cannabis addiction. As remedial agents, they are used to an inconsiderable extent, and the obvious purpose and effect of this bill is to impose so many restrictions on their use as to prevent such use altogether. Since the medicinal use of cannabis has not caused and is not causing addiction, the prevention of the use of the drug for medicinal purposes can accomplish no good end whatsoever.”

But it was to no avail, and the Marihuana Tax Act gained cultural currency, aided and abetted by a muckraking media. And Anslinger was far from done. Later, he harnessed the codierable powers and war chests of Andrew Mellon, Andrew Hurst, and other wealthy industrialists to oppose the use of hemp and marijuana. These men were more than happy to give Anslinger their support, who provided a thin patina of moral outrage to masks their otherwise naked plutocratic ambitions to establish monopolistic control over competitors.

Anslinger had his opponents to be sure. Fiorello La Guardia, who served as mayor of New York from 1934 to 1945, suspected that Anslinger was up to no good and sought to set the record straight.

After forming a commission to carefully study marijuana use for several years, he published a report, concluding, “The practice of marihuana does not lead to addiction in the medical sense of the word… The sale and distribution of marihuana is not under the control of any single organized group…The use of marihuana does not lead to morphine or heroin or cocaine addiction… Marihuana is not the determining factor in the commission of crimes… Juvenile delinquency is not associated with the practice of smoking marihuana…Marihuana is not the determining factor in the commission of crimes.”

Anslinger immediately pounced on the report, working to undermine its validity and conclusions. As Jason Martin writes, “Anslinger reacted to the report scathingly, arguing that it was not based on sound science. This critique was ironic, of course, since Anslinger’s unsubstantiated fear mongering and completely unscientific studies’ were the entire premise for launching the war on drugs.”

Anslinger’s crusade against marijuana was bolstered by the Boggs Act, passed in 1951. Although it was an amendment to strengthen the Narcotic Drugs Import and Export Act, it became the prototype for future mandatory minimum sentences associated with marijuana and other drugs. The Student Marijuana Alliance for Research and Transparency frames it this way:

“The law, named after future House majority leader Hale Boggs, severely lengthened the average sentence, often by several fold. The Boggs Act also made no distinction between consumers and traffickers, and it marked the first time that cannabis and narcotics were lumped into the same category. By treating cannabis as harshly as heroin, simple cannabis possession required a minimum of two years in prison and as many as five, plus a $2,000 fine. Second offenses increased the minimums to five to 10 years, while strike three jumped to 10 to 20 years.”

Undaunted, Anslinger pushed forward by supporting the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, an attempt to codify drug enforcement globally. Although sold as a means to provide treatment for people addicted to dangerous substances and held under the auspices of the United Nations to give it credibility, marijuana once again became enmeshed in the gears of justice, this time on the international level.

At the conclusion of the conference, the report The Plenipotentiary Conference for the adoption of a Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs was issued, stating, “Moreover, the Convention stipulates that after a definite transitional period, all non-medical use of narcotic drugs, such as opium smoking, opium eating, consumption of cannabis (hashish, marijuana) and chewing of coca leaves, will be outlawed everywhere. This is a goal which workers in international narcotics control all over the world have striven to achieve for half a century.”

Although Anslinger eventually retired in 1962, after supplying Joseph Raymond McCarthy with morphine to feed his growing addiction, his later years were marred by an ironic turn of events. According to Wikipedia, “In his later years Anslinger also suffered a mental breakdown characterized by intense paranoia and irrational thoughts, such as believing that addiction was ‘contagious’ and addicts had to be ‘quarantined’ or talking about ‘secret plots’ throughout the world; he was eventually hospitalized because of this breakdown.”

Anslinger’s work, however, established the basis for the final blow to the liberalization of marijuana– the title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act known as the Controlled Substances Act, established in 1970. This act made marijuana a Schedule I drug, which according to teh United States Drug Enforcement Administration, “have a high potential for abuse and the potential to create severe psychological and/or physical dependence,” and “have no currently accepted medical use.” Unfortunately, marijuana, along with the psychedelics LSD and Peyote, became demonized and conflated with drugs such as heroin and cocaine.

The consequences of the Controlled Substances Act are profound and troubling, providing the legal basis for extending the scope and depth of the War on Drugs. Most Americans are beginning to recognize the insidious nature of this war, particularly with regard to marijuana, along with its wider connection to incarceration and its attendant racial disparities.

Now, more than ever, Attorney General Garland needs to use his position of power to start to undo some of the damage wrought against a miraculous plant that shows promise not only medically, but as a salve for our socially and ethnically torn society.