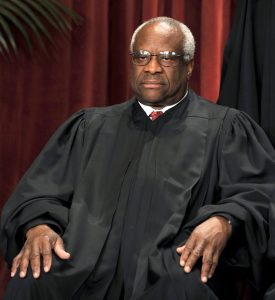

Our federal government gave another signal that legalization of marijuana is on the horizon for Americans. Building on the jurisprudence verbalized by Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY), has introduced legislation to decriminalize marijuana, paving the way for future legislation that fully legalizes and regulates the cannabis industry. As reported in the New York Times, the Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Act “. . . would remove marijuana from the Controlled Substances Act and begin regulating and taxing it, placing federal rules on a burgeoning industry that has faced years of uncertainty.”

Acknowledging the unofficial “marijuana holiday” of 4/20 on the floor of the upper chamber, the Senate majority leader stated, ““Hopefully, the next time this unofficial holiday, 4/20, rolls around, our country will have made progress in addressing the massive overcriminalization of marijuana in a meaningful and comprehensive way.” This legislative initiative builds on the preliminary work of the Marijuana Justice Act (S.1689), a bill introduced by Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ), in 2017. S.1689 would amend the Controlled Substances Act in the following manner:

- remove marijuana and tetrahydrocannabinols from schedule I; and

- eliminate criminal penalties for an individual who imports, exports, manufactures, distributes, or possesses with intent to distribute marijuana

Moreover, “[i]t prohibits and reduces certain federal funds for a state without a statute legalizing marijuana, if the Bureau of Justice Assistance determines that such a state has a disproportionate arrest rate or disproportionate incarceration rate for marijuana offenses,” and “directs federal courts to expunge convictions for marijuana use or possession.”

Finally, in a nod to push for recompense for the war on drugs, S.1689 would establish “in the Treasury the Community Reinvestment Fund” the proceeds of which may “ . . .establish a grant program to reinvest in communities most affected by the war on drugs.”

In 2017, Senator Booker stated emphatically, “Our country’s drug laws are badly broken and need to be fixed. They don’t make our communities any safer – instead they divert critical resources from fighting violent crimes, tear families apart, unfairly impact low-income communities and communities of color, and waste billions in taxpayer dollars each year.”

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) is also a co-sponsor of S. 1689. In 2019, Wyden echoed the sentiments of Booker, saying, “The War on Drugs destroyed lives, and no one continues to be devastated more than low-income communities and communities of color. There is a desperate need not only to correct course by ending the failed federal prohibition of marijuana, but to right these wrongs and ensure equal justice for people who have been disproportionately hurt.”

S.1689 dovetails with H.R.4815, introduced in 2018 by Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA-13). Titled the Marijuana Justice Act of 2018, the bill closely mirrors the language and intent of the Marijuana Justice Act of 2017.

In parallel fashion, Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-NY), reintroduced the Marijuana Opportunity, Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act in the U.S. House of Representatives in May with similar legislative aims. And although The House of Representatives previously passed the MORE Act in December 2020, the bill did not advance in the Senate.

Unfortunately for marijuana advocates, both the Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Act and the Marijuana Justice Act of 2018 will likely meet the same fate as the MORE Act, which failed to advance in the Republican-controlled Senate. Despite the fact that many of these Republican congressmen represent states that have medically or legalized marijuana, and actually are in favor of cannabis banking legislation reform, many are ethically opposed to marijuana reform at the federal level.

One of the figures who is staunchly opposed is Steve Daines (R-MT), who pushed back, stating, “The people in Montana decided they want to have it legal in our state, and that’s why I support the SAFE Banking Act as well — it’s the right thing to do — but I don’t support federal legalization.”

Not to be outdone, GOP Sen. Richard Shelby of Alabama, whose state legalized medical marijuana earlier this year, commented, “I think they can do other narcotics and things to relieve people’s pain and suffering.” By relieving suffering, is Shelby referring to being part and parcel of the opioid crisis that is tearing families apart, destroying individuals and communities, and consuming the soul of our country? The sheer ignorance and illogic of this statement and the future it advocates makes my frontal lobe, the seat of reasoning, prematurely atrophy!

This nonsensical stance seems to be ambivalent at best, and bordering on a form of dialectical schizophrenia at worst. If people in your state want marijuana to be legalized in some fashion, and the majority of states have legalized marijuana through medical or recreational avenues, what is the point of opposition, logically, legally, or morally?

It is obvious the will of Americans is tilted toward not only legalizing marijuana, but addressing the negative consequences of its prohibition. Are Republicans simply ignorant of the history around alcohol prohibition, which although also had lofty aims, ended tragically? And, how does the party that supports free enterprise, states rights, and a restriction on the intrusion of the federal government square their opposition with the overwhelming hypocrisy that renders its arguments flacid and meaningless?

The answer to these questions may stem from literature that supposedly indicates marijuana is associated with mental health issues, specifically schizophrenia–ironically. One of the most cited “authorities” is Alex Berenson, a former journalist and author of the book, Tell Your Children, his anti-marijuana opus that draws a fallacious causal link between marijuana use, schizophrenia, and violent behavior. Amongst other outrageous claims, Berenson asserts that :

- Marijuana use is linked to opiate and cocaine use. Since 2008, the US and Canada have seen soaring marijuana use and an opiate epidemic. Britain has falling marijuana use and no epidemic;

- THC—the chemical in marijuana responsible for the drug’s high—can cause psychotic episodes. After decades of studies, scientists no longer seriously debate if marijuana causes psychosis.

- Psychosis brings violence, and cannabis-linked violence is spreading. In the four states that first legalized, murders have risen 25 percent since legalization, even more than the recent national increase. In Uruguay, which allowed retail sales in July 2017, murders have soared this year.

Once again, my frontal lobe is seizing as it grapples with the illogic of both the argument and the evidence. To begin with, Berenson does not have a medical background. In and of itself, that does not disqualify his premises. Still, an authority ought to have some background that provides a sense of expertise.

More importantly however, Berenson’s claims suffer from the logical fallacy of cum hoc ergo propter hoc, Latin for “with this, therefore because of this.” Essentially, this fallacy confuses causation and correlation, a grievous error that undermines the very premises of scientific investigation. So let’s unpack these arguments.

Carl L Hart, the chairman and Ziff professor of psychology and psychiatry at Columbia University and author of High Price: A Neuroscientist’s Journey of Self-Discovery that Challenges Everything You Know About Drugs and Society, and Charles Ksir, professor emeritus of Psychology and Neuroscience at the University of Wyoming and author of Drugs, Society and Human Behavior, point out this fallacy in the article, Does marijuana use really cause psychotic disorders?

Hart and Ksir, both experts in their fields, write: “In our many decades of college teaching, one of the most important things we have tried to impart to our students is the distinction between correlation (two things are statistically associated) and causation (one thing causes another).” The authors further argue:

In our extensive 2016 review of the literature we concluded that those individuals who are susceptible to developing psychosis (which usually does not appear until around the age of 20) are also susceptible to other forms of problem behavior, including poor school performance, lying, stealing and early and heavy use of various substances, including marijuana. Many of these behaviors appear earlier in development, but the fact that one thing occurs before another also is not proof of causation.

Hart and Ksir ultimately concluded from both an extensive literature review and experimental data that “. . . aggression and violence are highly unlikely outcomes of marijuana use.” The authors also make a broader, yet darker point, one that connects the demonization of marijuana via race. The authors point out:

During congressional hearings concerning regulation of the drug, Harry J Anslinger, commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, declared: “Marijuana is the most violence-causing drug in the history of mankind.” He was compelling. But unfortunately, these fabrications were used to justify racial discrimination and to facilitate passage of the Marijuana Tax Act in 1937, which essentially banned the drug. As we see, the reefer madness rhetoric of the past has not just evaporated; it continued and has evolved, reinventing itself perhaps even more powerfully today.

To be fair, there is some corroborating research that links marijuana and violence. In the 2016 study, Continuity of cannabis use and violent offending over the life course, the authors, Schoeler, T, et al., conclude that the evidence provides a “. . . strong indication that cannabis use predicts subsequent violent offending, suggesting a possible causal effect, and provide empirical evidence that may have implications for public policy.” Notice, however, the tentative language of the conclusion. Words such as “suggesting,” “possible,” and “may” temper the veracity of the evidence.

Furthermore, there are other scientific studies that refute the premise of Schoeler and company. Helen White, a Distinguished Professor of Sociology with a joint appointment in the Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies and the Sociology Department, and Rolf Loeber, Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh until his death in 2017, authored the study Teasing Apart the Developmental Associations Between Alcohol and Marijuana Use and Violence. White and Loeber reached the same conclusion as Hart and Ksir, stating: “ . . . the relationship between frequent marijuana use and violence (and vice versa) was spurious; it was no longer significant when common risk factors such as race/ethnicity and hard drug use were controlled for. We conclude that the marijuana-violence relationship is due to selection effects whereby these behaviors tend to co-occur in certain individuals, not because one behavior causes the other; rather, both are influenced by shared risk factors and/or an underlying tendency toward deviance.”

Regardless of what you believe about the apparently conflicting scientific evidence and the association between marijuana prohibition and race, there is a more philosophical, universal issue we must come to terms with in the United States. Either we live in a country that maximizes personal freedoms as enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, or we don’t. Either we honor Federalism as a primary guiding political principle, or we don’t.

And though we sometimes dramatically fall short of our founding philosophical goals, we have to keep striving to achieve them. I’ll leave you with the wise words of Justice Thomas regarding the inconsistencies undergirding opposition to change: “Once comprehensive, the Federal Government’s current approach is a half-in, half-out regime that simultaneously tolerates and forbids local use of marijuana. This contradictory and unstable state of affairs strains basic principles of federalism and conceals traps for the unwary.”