Hashish will be, indeed, for the impressions and familiar thoughts of the man, a mirror which magnifies, yet no more than a mirror. – Charles Baudelaire

At the core of marijuana use is the inescapable need to elude the drudgery of daily reality. Oh sure, there is the undeniable connectedness, a feeling of emotional openness, and a sense of grandiosity that accompanies a good high. But the reality is these are merely aspects of escapism. There is something satisfying about taking risks, about not always playing it safe, even if it is only for a few hours. As Edgar Rice Burroughs once wryly observed, “If I had followed my better judgment always, my life would have been a very dull one.” For some cannabis users, the suspension of better judgment became a compulsive and ruinous habit.

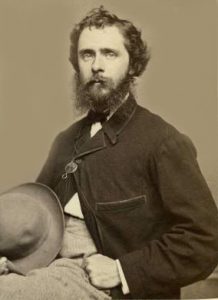

Such was the case for Fitz Hugh Ludlow.

Born September 11, 1836, in New York City, Ludlow was raised by abolitionist parents who likely instilled a sense of rebelliousness that caused feelings of wanderlust, leading the young Ludlow to follow Albert Bierstadt, a German landscape painter, across the Rocky Mountains into the great and unknown expanse of the developing American West. As the trek unfolded, Ludlow encountered Mormons in Salt Lake City, revealing his petty prejudices. Incapable of processing their polygamous lifestyles and unquestioning acceptance of Brigham Young’s leadership, Ludlow wrote,” “[i]n their insane error, [the Mormons] are sincere, as I fully believe, to a much greater extent than is generally supposed. Even their leaders, for the most part, I regard not as hypocrites, but as fanatics.”

Ludlow also wrote poetry and short fiction with moderate success at best. However, he is best known for writing The Hashish Eater, a 300 plus page rambling, semi-lucid treatise on his experiences with ingesting large amounts of hashish. With The Hashish Eater, Ludlow unleashed his imagination in a style that presaged Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception and the psychedelic experimentation of the 1960’s counterculture.

Ludlow and The Hashish Eater

American scholar, historian, biographer, essayist, and often a critic of Ludlow’s writing, Morris Bishop observed the following about The Hashish Eater:

He finds lyric phrasing to convey the unearthly beauty of his visions, and the unearthly horror of the evil fantasia which succeeded his bliss. He is a drugged Dante in reverse, descending from the Paradiso to the Inferno. His descriptions, drawing from his subconscious a strange mingling of the sublime and the grotesque, often suggest the work of Dali and other surrealists. The writer’s passion gives his work an intensity which the reader recognizes and sympathetically feels. This is a very considerable literary achievement.

Ludlow’s interior journey begins in a dreamy, esoteric, cosmological manner:

I stood in a remote chamber at the top of a colossal building, and the whole fabric be- neath me was steadily growing into the air. Higher than the topmost pinnacle of Bel’s Babylonish temple—higher than Ararat—on, on forever into the lone- ly dome of God’s infinite universe we towered ceaselessly. The years flew on ; I heard the musical rush of their wings in the abyss outside of me, and from cycle to cycle, from life to life I careered, a mote in eternity and space.

Yet, so obsessive was Ludlow with both the frequency and quantity of hashish, his spiritual and dreamy involution gradually gave way to an all-consuming nightmare of darkness and fear, a descent into bowels of an inner hell in which Ludlow was crippled by paranoia and unnerving feeling that his very essence was being fractured and atomized. In Ludlow’s words:

…the soul withers and sinks from its growth toward the true end of its being beneath the dominance of any sensual indulgence. The chain of its bondage may for a long time continue to be golden—many a day may pass before the fetters gall—yet all the while there is going on a slow and insidious consumption of its native strength, and when at last captivity becomes a pain, it may awake to discover in inconceivable terror that the very forces of disenthralment have perished out of its reach.

Unable to get a handle on his fleeting sense of self, Ludlow’s psyche became unmoored from waking reality, causing him to face his deepest fears– himself: “Crouching upon a step, glaring upon me between the posts of the balustrade, clutching at me like a tiger-cat, sat—myself again! I rushed toward the door of another room; I would lock myself in from my multitude of being. At that door, tearing his hair, gnashing his teeth, smiling with a maniac smile of pain, stood once more myself!”

Unfortunately for Ludlow, his hashish hell was merely a pit stop on a drug-laden train that ended in addiction to opium. And although he dedicated his last few years of life to treating other opium addicts, Ludlow was so consumed by his addictions that he ultimately died an addict at the age of 34.

In the end analysis, I do not see this as a warning against the use of marijuana. I still believe that for most people, cannabis is at the very least a valid stress reliever.

And it’s probably too simplistic and obvious to say that excess is the road to ruin. We live in a time in which the tragedy of the drug crisis of our country is imbued upon our consciousness through television and social media for most people, and for many, through personal experience.

But perhaps the takeaway is this: When it comes to smoking weed, always maintain some sense of control by using it to your advantage. When you glimpse the face of God or witness the origins of the universe, when you feel connected to every person and star in the heavens, when you ask, as Edgar Rice Burroughs did, Am I alive and a reality, or am I but a dream?, don’t squander the opportunity by pushing yourself deeper into the abyss.

Instead, harness the vision. Write the poem, play, or novel that has been nibbling at your consciousness. Pick up your palate and paint the angels or devils, create the seven-course gourmet meal you’ve been telling your family and friends about for the past few years.

I’ll leave you with the words of Ludlow himself:

What we want, we have for our pains

The promise that if we but wait

Till the want has burned out of our brains,

Every means shall be present to state;

While we send for the napkin the soup gets cold,

While the bonnet is trimming the face grows old,

When we’ve matched our buttons the pattern is sold,

And everything comes too late-too late.

We would just love it if you took some time out of your day and answered a few questions for us. You can help us bring you content that you are more interested in. Also, keep on the lookout for new, more interactive ways to engage with Newsweed.

Give us your thoughts by completing our survey.